Charles Bradford Hudson

2011/05/27 § 1 Comment

Charles Bradford Hudson

The Quiet Impressionist

by Jeffrey Morseburg

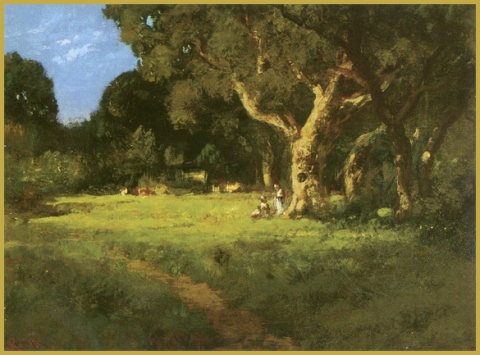

Charles Bradford Hudson (1865-1939) was a quiet painter. While a number of his artistic comrades on the Monterey Peninsula were gregarious bohemians, he was content to let his art speak for itself. Although Hudson was one of the first residents to adopt the broad palette of Impressionism for his landscapes, his approach reflected his precise, careful, scholarly nature. His paintings often focused on what may be best described as the quiet side of nature, the native flowers and grasses that grew in the sandy soil along the coast. His solidly structured compositions, elegant draftsmanship and exquisitely applied brushwork stand in stark contrast to the dramatic views of the windswept cliffs that many of his contemporaries painted.

Hudson was born in Oil Springs, Ontario, Canada, where his parents lived temporarily, and he grew up in Washington D.C.. His father was John Jay Hudson and his mother was Emma Little Hudson. Hudson’s family had deep roots in America, descending from William Bradford, the Colonial Governor of Massachusetts. Because his father was academically inclined, Hudson was a scholarly boy, fascinated by history, science and art.

Because education was important to his family, he took a degree at Washington’s Columbian University before moving to New York, where he studied at the Art Students League under George DeForest Brush (1855-1941), famed for his Indian subjects and with Munich-trained William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). In 1893, Hudson embarked for Paris, where he enrolled at the Academie Julian. He studied at the private school under William Adophe Bouguereau (1825-1905), one of the great academic masters of the era. Because Hudson was a talented and observant writer, he was able to pay for his art education by serving as a correspondent for the Atlantic, one of America’s premier intellectual publications. By the time he left Europe, Hudson’s work had developed to the point where it would later be included in the International Exposition in Bergen, Norway in 1898 and the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, with his work earning a silver medal in each fair.

When Hudson returned from Europe he began a career in illustration, providing pictures for national magazines and books. Two of the books that he illustrated were “The Forging of the Sword” and other poems by Juan Lewis in 1892 and “A Ranch on the Oxhide.” He also continued writing articles for periodicals like Cosmopolitan and the Atlantic.. Hudson married Christine Schmidt (1869-1972) in 1893 and the following year they had a son, Lester J. Hudson (1894-1974), but the relationship didn’t last.

Hudson had always been interested in the natural world, and he found a second calling by painting illustrations of fish and animals for scientific publications. He illustrated a scholarly work on the preparation of specimens for display in 1891. Because of the quality of his work and his dedication, Hudson was hired to go on expeditions funded by the Bureau of Fisheries. On trips to the Caribbean, the Great Lakes, the rivers of California and the Pacific Coast, he would paint examples of fish as they were caught and identified.

Hudson worked closely with the naturalist David Starr Jordon, first president of Stanford University, who wrote a number of scholarly works on fish with Dr. Barton W. Everman of the Bureau of Fisheries. On a trip to Hawaii with Jordon the artist met a young San Jose schoolteacher named Claire Grace Barnhisel, who was on her way to the islands to teach, and a romantic relationship blossomed between artist and teacher. After working with Hudson on a number of scientific expeditions, Jordon described him as the world’s finest illustrator of marine life – someone who could combine accuracy and beauty – and some of the scholarly volumes they collaborated on are highly sought- after collector’s items today.

In 1898 Hudson put his illustrations, easel paintings and scientific collaboration on hold to join the ranks of volunteers for the Spanish-American War. Commissioned as a lieutenant, he was sent to Cuba, participated in the victorious Siege of Santiago, and then served on the staff of Col. George H. Harries, who led the 1st District of Columbia Infantry. Because the war was so short, the unit saw little action, but Hudson distinguished himself enough to be promoted to Captain, and many people referred to him as “Captain Hudson” for the rest of his life.

Hudson was introduced to the Monterey Peninsula through his scientific work, for even then the region was famous for the incredible variety of marine and mammalian species that populated its shores and sea. The artist was drawn to the area purchasing a home in Pacific Grove, where he brought his new wife Claire after their marriage in December of 1903. Once settled in the coastal hamlet, Hudson began to paint scenes of the sand dunes and flora of the peninsula as well as the ocean, often with the subtle effects of the setting sun. He exhibited at the Del Monte Art Gallery in Monterey, with the local art organizations and sent paintings north to exhibitions at the Bohemian Club and at Gump’s, the antique dealer in San Francisco.

After moving to the Peninsula, Hudson came to love and romanticize the days of the “Californios,” as the residents of Alta California called themselves before the Americans gained control of the state in 1848. In 1915 he did an article for Sunset Magazine titled “California on the Etching Plate” where he wrote wistfully about the days of the Carmel Mission and the Monterey Presidio. Hudson illustrated the article with etchings of some of the historic adobes of the peninsula. Because of his historical interest in early days of Monterey, he became an early preservationist list and an advocate for the timeless Spanish methods of building.

Fortunately, Hudson’s interest in historic preservation was passed onto his children. His oldest son, Lester, lived in Washington D.C., but spent summers with his father in California. While on vacation at one point he met a local girl, Margret MacMillian Allen, who became his wife. The Allens were enlightened ranchers who owned a large parcel of land south of Carmel, which included the dramatic cliffs and bays of Point Lobos. During and after his long and distinguished naval career, Admiral Hudson and his wife were active in preservation efforts and instrumental in the Allen family’s deeding Point Lobos to the state of California.

Settled in his cozy home and studio near the Asilomar resort, Hudson wrote two books, “The Crimson Conquest” (1906) which was a romanticized telling of Pizzaro’s conquest of Peru and “The Royal Outlaw” (1917) a novel for young adults on the biblical story of King David. He continued to write magazine articles and during World War I he wrote a analysis on German militarism for the New York Times Magazine.

After the San Francisco Earthquake the entire city had to be rebuilt, and one of the last major structures to be completed was the San Francisco Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park. Hudson painted some of the large murals that served as the backdrops for the dioramas featuring mounted specimens of the animals of the coast and islands of California. When the academy finally opened in 1916, Hudson’s work was highly praised and remains on display today.

When the Carmel Art Association was formed in 1927, Hudson became a member, and he continued painting into his 60s, even as the artistic elite turned their back on the traditionalist painters. In 1939, the year of the artist’s death, San Francisco hosted the Golden Gate International Exposition. Held twenty-four years after the Panama-Pacific Exposition, this was the San Francisco’s second World’s Fair, and Charles Bradford Hudson’s works were included.

Hudson’s works are rarely on the market, as many remain in the collections of his distinguised family. His artistic oeuvre includes scenes of Monterey, Carmel, Asilomar, the southern California coast an the Mojave Desert, all beautifully painted and subtly colored. An in-depth biography of Charles Bradford Hudson is being perpared by scientist Victor G. Springer of the Smithsonian Institution and author Kristin Murphy. This book will cover his life, artistic and literary accomlishments and numerous contributions to science.

William Keith: From the Grandiose to the Intimate

2011/05/27 § 3 Comments

William Keith

From the Heroic Landscape to Tonalism

By Jeffrey Morseburg

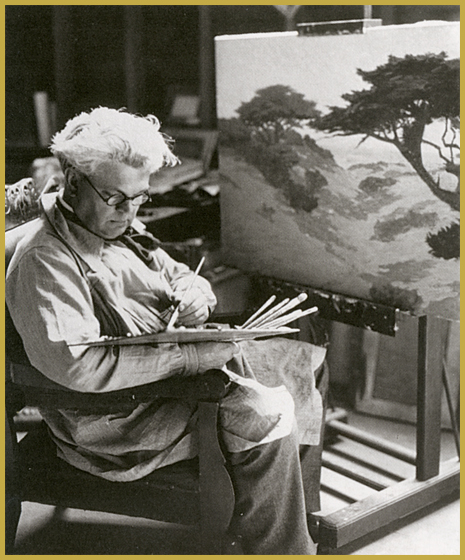

William Keith (1838-1911) is the seminal figure in the history of early California painting. For contemporary viewers, attuned to the colorful palette of California Impressionism, the appeal that Keith has to art historians and collectors may be difficult to understand at first glance. After all, his Barbizon-inspired works were often painted in a narrow tonal range and many of the late works are dark, even murky. However, as viewers become more familiar with his career and the breadth of his artistic output, they should come to understand why Keith was the dominant figure in California painting for several decades and why his best works can be ranked among the great masterpieces of 19th-Century American landscape painting.

William Keith was born in Aberden, Scotland in 1838. He was raised in a strict Presbyterian environment first by his maternal grandparents and then by his mother. In 1852, while he was a teenager, Keith emigrated to America with his mother and sisters. They made their way to New York, where his maternal uncle, William Bruce, had settled. Like many other artistically talented boys of his era, he quit school at an early age and was apprenticed to a wood engraver before joining the Harper Brothers publishing firm.

During Keith’s formative years, New York was the thriving artistic capital of America. The Hudson River School of Romantic landscape painters dominated the artistic scene and the National Academy of Design, which was the main American exhibition venue. The young Scottish emigrant’s artist apprenticeship and early professional career coincided with the triumphs of Frederick Church (1826-1900) and his great rival Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). Church ventured to Central and South America and his romantic pictures of the Andes became a sensation while Bierstadt’s enormous canvasses of the Rocky Mountains brought him fame if not always critical success. Keith ventured west to California in 1859, settling in San Francisco, where he began to scratch out a living as an engraver. It was there that he took his first formal painting lessons, from the noted portrait painter Samuel Mardsen Brooks (1816-1892).

Keith’s growing success in the engraving business enabled him to marry fellow artist, Elizabeth Emerson, in 1864. Two years later he began to exhibit his watercolors professionally. Keith’s chosen medium and the naturalistic handling of his subjects reflect his familiarity with the works and ideals of the British author and painter John Ruskin (1819-1900) and the English movements he influenced. His early works were of Marin County, the domesticated countryside just north of San Francisco, but by 1867 he was painting in the Sierra Nevada, which would become the subject of his greatest works. Soon, the young artist began working in oils, but his early efforts in this medium were somewhat crude and labored. On his sketching trips, he usually worked in oil on paper, waiting until he returned to his San Francisco studio to work the sketches up on canvas. Keith became an experienced outdoorsman, and in early 1869, a commission took him on an extended sketching trip throughout the wilderness of the Pacific Northwest.

Realizing that he needed further formal training, Keith held a successful auction of his works, and in the fall of 1869 left for Europe. In that era, many American painters who aspired to landscape painting chose to study in Dusseldorf, rather than Paris, so it was there that Keith went to study with Albert Flamm (1823-1906). Although Keith’s stay in Europe was brief, lasting less than a year, his formal work with Flamm and his exposure to European exhibitions introduced him to a wide range of artistic styles and helped him to reach artistic maturity.

Keith returned to the United States in 1871. He first painted in rugged Maine, where dozens of the successful New York painters summered. Then opened a studio in Boston. Keith’s large paintings of California began to win him some good notices and a following of patrons. He exhibited major paintings of Mount Tamalpais and Mount Shasta at the National Academy of Design, which were then sold to prominent California collectors. In 1872 Keith returned to San Francisco, a mature and experienced painter. He found that his competitor Thomas Hill (1829-1908) had also returned from a period of study and that in addition the Eastern painter Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) had opened a studio for an extended stay in the west. Together, these three painters built a wide following for their monumental scenes of the Sierra Nevada and other California subjects. Their major works were artistic expressions of the philosophy of American expansionism. As cities were transformed by the forces of the industrial age, the works of Keith and other landscape painters began to reflect an appreciation for the grandeur of the western landscape. Keith’s artistic philosophy was also shaped by his friendship with the naturalist John Muir, whom he accompanied on extended treks through the wilderness.

Elizabeth Keith, the artist’s wife, died in 1882. After marrying the amateur artist Mary McHenry, a restless Keith returned to Europe in 1883, now with the intention of mastering portraiture. Always attracted to a broad technique and darker tonalities, Keith ventured to Munich, where these characteristics were still favored. He opened his own studio in the Bavarian capital and had his work critiqued by some of the leaders of the Munich school. The expatriate American painter J. Frank Currier (1843-1909), for example, encouraged Keith to try a more experimental approach to painting the landscape. This second European sojurn’s exposure to new ideas had a lasting effect on the California atist, and he began to adopt a much more evocative style.

The William Keith that returned to San Francisco was a changed artist. In his later work, influenced by the stay in Munich and the works of the Barbizon painters that he had seen in Paris, Keith placed more emphasis on the mood of his chosen subject and paid less attention to the topography of the landscape. He began to paint simple scenes of sheep grazing on the hills of Marin County or cattle lying in the shady glen. He no longer sought to find the “truth” of nature, but to paint its moods. Unfortunately, these more interpretive paintings did not please the public as much as the more heroic depictions of nature that he had done in earlier years, and Keith went through a period of depression.

In 1891 George Inness (1823-1894), the American Tonalist painter, came west to San Francisco and changed the course of Keith’s career. Keith had been influenced by the writings of Inness, and the two artists shared not only a similar artistic outlook, but even the same Swedenborgian religious philosophy. Inness’s visit lifted the California artist’s spirits and the two men traveled together, shared Keith’s studio, and held a joint exhibition in San Francisco. Keith learned a great deal from Inness, whose stature in American art helped justify the change in style that western audiences had found inscrutable.

As the 1890s progressed, Keith’s popularity grew, and he became one of the most prosperous and respected members of San Francisco’s artistic community. In 1893 his works were exhibited in the Chicago World’s Fair, and he made another extended trip to Europe. Keith’s poetic, pastoral pieces were sold to California’s elite. While Keith painted some masterful paintings in his later years, his artistic oeuvre is littered with poorly composed and overly gloomy landscapes, many of which have turned even darker with the passing of time. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire destroyed Keith’s studio and, tragically, two thousand of his paintings. Unfortunately, many of Keith’s important early works were lost in the conflagration, which also destroyed the homes of most of the important San Francisco collectors. Keith managed to recover from the loss, however, and continued painting until a short time before his death in 1911.

William Keith’s artistic philosophy changed dramatically in the course of his long life. moving from the grandiose to the intimate. He began his career as a painter of the heroic landscape, celebrating California’s beauty and grandeur. As the frontier period of American history closed, and the west was domesticated, Keith turned from a romantic approach to a more subjective and poetic view of nature and he seems to have been the only notable California painter who made this type of transformation. Copyright, 2001-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without the specific written permission of the author. This entry adapted from my brief essay in the California Art Club’s Gold Medal Exhibition Catalog from 2001.

The Silence and Solitude of Granville Redmond

2011/05/18 § Leave a comment

Granville Richard Seymour Redmond

From Silence and Solitude to Sunlit Poppies

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Rendered deaf and speechless by scarlet fever at age three, Granville Redmond (1871-1935) communicated with the world through the visual language of his art. Although he was personally drawn to ‘pictures of silence and solitude,’ his Barbizon inspired landscapes did not reach the same heights of popularity that his colorful paintings of California poppy fields achieved.

Redmond’s early works were moody depictions of the southern California landscape. Gradually his palette brightened and his work became more painterly as he came under the spell of Impressionism. Many of Redmond’s mid-life works were painterly, with brighter colors, but they remained part of the tonalist aesthetic. In the final stages of his career, the artist’s palette became intensely colorful, and he relied on a surface that was thick with impasto, giving his paintings a decidedly post-Impressionistic quality.

Granville Redmond was born in Philadelphia in 1871. The Redmond family moved to San Jose, California, and shortly thereafter, they enrolled Granville in the California School for the Deaf in Berkeley. His teacher, a naturalist named Theophilus Hope d’Estrella, recognized Granville’s artistic talent and saw to it that the boy received the encouragement he deserved.

After his graduation from the school for the Deaf in 1890, he was awarded funds to attend California School of Design, where he studied under Arthur Matthews, a leader in the Northern California Arts and Crafts movement. In 1893 another scholarship allowed him to venture to Paris, where he attended the Academie Julian, rooming with the deaf sculptor, Douglas Tilden.

In 1895, Redmond had the distinction of having his huge painting, Matin d’Hiver, accepted to the Paris Salon, an impressive feat for a young American painter. In 1898, he returned to California, settling in Los Angeles, where he met and married a deaf woman, Carrie Ann Jean.

In Los Angeles, Redmond lived in the Highland Park area and painted with Elmer Wachtel and Norman St. Clair. Established in southern California, he began to forge a career as a painter and gained a reputation for his landscapes. In 1908, Redmond moved bacck north where he often painted with Xavier Martinez (1816 – 1943) and his old friend from the School of Design, Gottardo Piazzoni (1872 – 1945).

Because of his deafness, Redmond was gifted in the art of pantomime and he utilized his skill to garner work in the silent film industry. Redmond developed a friendship with the famous actor, Charlie Chaplin, who learned pantomime routines from the deaf painter, and used Redmond in some of his films. In addition, Chaplin gave Redmond a studio in which to paint that was located on the movie studio lot. He painted throughout southern California, from the Laguna surf to the poppy fields in the high desert. Redmond’s usual sensitivity to nature is evident in every work, whether it is a luminous painting of the surf lit by the moon, a quiet pol in the late afternoon, or the hills of poppies and lupine for which collectors still clamor. Copyright 2001-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, 2001-2011, not to be reproduced without author’s specific written permission.