Benjamin Chambers Brown

2011/06/02 § 1 Comment

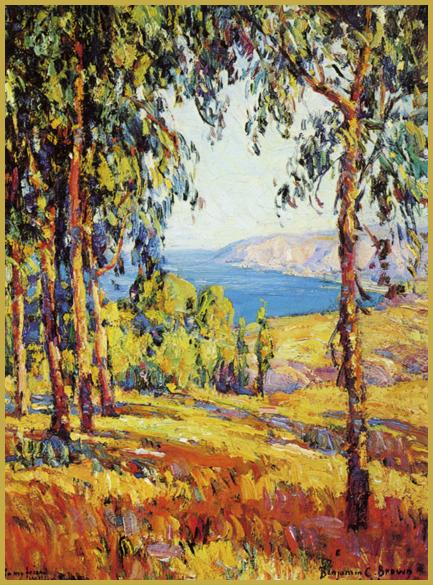

Benjamin Chambers Brown

Dean of Pasadena Painters

By Jeffrey Morseburg

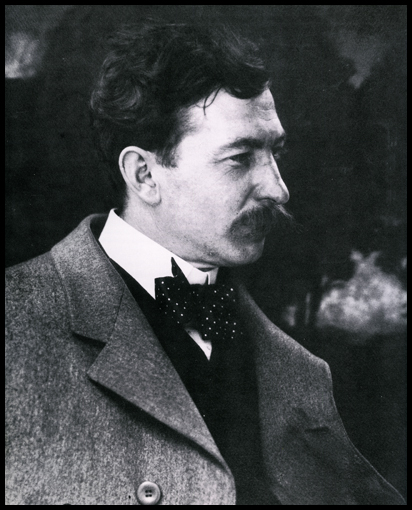

Benjamin Chambers Brown (1865-1942) was known as ‘The Dean of Pasadena Painters.’ He was one of the leaders of Pasadena’s artistic and intellectual community for more than forty years and a vital figure in Southland art. Brown’s earliest works exhibit the influence of the tonalist aesthetic, but soon after settling in California he adopted the painterly brushwork and chromatic palette of Impressionism.

Benjamin Brown was born in Marion, Arkansas, and he received his initial training at the St. Louis School of Fine Art. Trained in photography, Brown made his first trip west in 1885. He sketched in and around Los Angeles, but returned to St. Louis, unable to make a living in Southern California, which then has a very small circle of collectors and a lack of exhibition venues. Brown then sailed for Paris, where he studied for a year at the Academie Julian.

After he arrived back in St. Louis he struggled to build a following for his still-lifes until he and his family moved west to Pasadena, arriving in the San Gabriel Valley around 1895. In his early years in the Southland he painted with the limited palette and closely-related values of Tonalism, but as Impressionism took hold in California, his palette brightened and his brushwork loosened. Brown took on students in order to augment his income from art sales and one of them was Eva Scott Fenyes (1846-1920). Both Benjamin Chambers Brown and his younger brother Howell Brown, who concentrated on printmaking, maintained a long friendship with Eva Scott Fenyes (1896 – 1930), the amateur watercolorist and one of Pasadena’s most important patron of the arts.

Brown was a tall, gaunt man with an eccentric personality. He was a gentle soul and like his brother Howell, he was a lifelong bachelor and the siblings lived with their mother until her death. The Brown home was the site of artistic discussions and hosted a salon for Pasadena intellectuals. The Brown brothers were founders of the California Society of Printmakers and helped popularize the graphic arts in Southern California. Like John Gamble (1863 – 1957) and his friend, Granville Redmond (1871-1935), Benjamin C. Brown’s paintings of California poppies became popular with collectors. At the turn of the century, the spring rains would bring bright fields of poppies to the Altadena meadows above Pasadena. Brown only had to venture a short distance from his home to paint the swaying eucalyptus and golden poppies.

Brown was also one of the founders of the California Art Club, which helped to popularize the Impressionist style in Southern California and he served as its President from 1915 to 1916. Later in their lives, the Brown brothers made extended trips to Europe and North Africa, where they painted and sketched. In California, he painted frequently along the coast- in Yosemite and the high Sierras. Brown also traveled east to the desert near Palm Springs to paint, a favorite spot for many San Gabriel Valley painters. The elderly Pasadena artist continued to paint and make prints through the years of the Great Depression and died in Pasadena in 1942. Copyright 2001-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without the specific written permission of the author.

Victor Matson: Plein-Air Painter of South Pasadena

2011/06/01 § Leave a comment

Victor Matson

Plein-Air Painter of South Pasadena

President of the California Art Club

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Victor Stanley Matson (1895-1972) was one of the most prominent of the second generation of California plein-air landscape painters. Matson began exhibiting his work in the early 1930’s and was a tireless advocate for the plein-air tradition, serving as an officer in virtually every Southern California arts organization, most prominently as President of the venerable California Art Club. Recognized for his scenes of the Mojave desert and the local foothills, the South Pasadena painter was also an early fine Camera Pictorialist photographer and a printmaker.

Victor Matson was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1895. Not much is known of his early life. Apparently, he attended a military school during his high school years and he may have been trained as a flyer during the First World War as photos of him in flying gear from that time period were part of his estate. He graduated from the University of Utah about 1917 with a degree in engineering. Matson showed promise in the arts and he received training in drawing, perspective, drafting and rendering during the course of his studies.

Matson moved to southern Califonria in 1922, initially settling in Long Beach . In 1924, he and his wife, Virginia, purchased a house in South Pasadena, bordering Alhambra Park and the Los Angeles suburb of Alhambra. In those days, Alhambra had a very active fine arts community, with Jack Wilkenson Smith (1873-1949), Frank Tenney Johnson (1874-1939) and Clyde Forsyth (1885-1962) presiding over a small artists’ colony. The Alhambra painters all lived on Champion Place, a small, eucalyptus-lined street on the edge of a wash, bordering the San Gabriel Country Club where Matson visited frequently.

Nestled in cozy South Pasadena, Matson began work as an engineer for the City of Los Angeles and began to study art with a number of California painters. He studied with W.T. McDermitt (1884-1961)at the Businessman’s Art Institute near downtown Los Angeles, before he headed home to South Pasadena in the evenings. Matson studied privately with Trude Hascomb and Jack Wilkenson Smith. He learned printmaking from Franz Geritz (1895-1945), who taught at the University of Califrnia Extension in Los Angeles. It was Jack Wilkinson Smith, however, who had the greatest influence on Matson’s developing plein-air work. Matson accompanied Smith and his fellow painters on many sketching trips to the San Gabriel Mountains and the Mojave Desert, north of Palm Springs , a favorite location for the Alhambra painters. Sam Hyde Harris was also a major influence on Matson and a life-long friend.

Matson became part of the declining Arroyo Seco Arts and Crafts culture based in Pasadena and Highland Park. He exhibited frequently with all of the major southern California arts organizations from the 1930’s through the 1960s. Matson won dozens of awards in local and regional exhibitions, including the Purchase Prize at the California Statewide Exhibit in both 1943 and 1946. He had solo exhibitions at the Los Angeles Arts Center, the Alhambra City Hall, the Glendale Art Association and the Beverly Hills Women’s Club. In 1965, a special exhibition was held for Matson at the Los Angeles City Hall. As the first generation of the California plein-air painters died and the art world changed, the museums no longer welcomed exhibitions of plein-air impressionism, which they viewed as retrograde and conservative. Thus, the painters had to rely on smaller, less prestigious venues in order to exhibit their work and attract collectors. Matson participated in many group exhibitions at the Greek Theatre, the Duncan Veil Galleries, the Friday Morning Club, Bullocks Department Store, the Pasadena City Library, the Eden Club, the Hollywood Women’s Club, the Selan Gallery, as well as local banks.

Matson and his wife, Virginia, were incredibly active in organizing exhibitions and running the various arts organizations that he belonged to. He served on the advisory Board for the California State Fair and was President of the California Art Club, the San Gabriel Art Association and the Valley Artists’ Guild. Matson was actively painting and exhibiting until shortly before his death in 1972.

Victor Matson worked primarily out-of-doors. He began all of his work on location, even quite large paintings. Because he worked out-of-doors, he limited his largest works to about 26×32 inches. He didn’t like to paint small canvases, so works are rarely smaller than 18×24 inches. After beginning a painting on location, he would often complete the work in his upstairs studio. He augmented his location work in oil with pencil sketches and reference photographs.

Matson painted more scenes of the Mojave than any other subject, working around Palm Springs and Indio and in the Coachella Valley. He painted marines infrequently on trips to the Southern California Coast or when he traveled north to Monterey . On vacations to the eastern United States, Matson painted scenes of the fall colors and snow scenes. His palette was conservative and subdued in color and his best works exhibit the airy, atmospheric quality that is the hallmark of the plein-air style. Matson’s style of painting was honest and straightforward, never particularly mannered or stylized, characteristics which reveal the strong influence of Jack Wilkenson Smith.

Matson’s photographs have an altogether different quality, for they are primarily dreamy, diffused works that reflect the influence of the tonalist movement on the early fine arts photographers. His books of pencil sketches show Matson’s great facility for drawing and his accurate draughtsmanship. Matson’s engineering training seems to have kindled a great affection for architectural detail, as the many of his plein-air pencil sketches depict buildings, often nestled in mountain settings.

Victor Matson played an important role in the preservation and the continuation of the plein-air tradition. His works were painterly but accurate transcriptions of what he saw on location, whether it was a house in the San Gabriel foothills, a stand of Monterey Pines on the Carmel coast or a portrait of a single smoke tree in the arid California desert. Copyright 1992-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without express written permission of the author.

Charles Bradford Hudson

2011/05/27 § 1 Comment

Charles Bradford Hudson

The Quiet Impressionist

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Charles Bradford Hudson (1865-1939) was a quiet painter. While a number of his artistic comrades on the Monterey Peninsula were gregarious bohemians, he was content to let his art speak for itself. Although Hudson was one of the first residents to adopt the broad palette of Impressionism for his landscapes, his approach reflected his precise, careful, scholarly nature. His paintings often focused on what may be best described as the quiet side of nature, the native flowers and grasses that grew in the sandy soil along the coast. His solidly structured compositions, elegant draftsmanship and exquisitely applied brushwork stand in stark contrast to the dramatic views of the windswept cliffs that many of his contemporaries painted.

Hudson was born in Oil Springs, Ontario, Canada, where his parents lived temporarily, and he grew up in Washington D.C.. His father was John Jay Hudson and his mother was Emma Little Hudson. Hudson’s family had deep roots in America, descending from William Bradford, the Colonial Governor of Massachusetts. Because his father was academically inclined, Hudson was a scholarly boy, fascinated by history, science and art.

Because education was important to his family, he took a degree at Washington’s Columbian University before moving to New York, where he studied at the Art Students League under George DeForest Brush (1855-1941), famed for his Indian subjects and with Munich-trained William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). In 1893, Hudson embarked for Paris, where he enrolled at the Academie Julian. He studied at the private school under William Adophe Bouguereau (1825-1905), one of the great academic masters of the era. Because Hudson was a talented and observant writer, he was able to pay for his art education by serving as a correspondent for the Atlantic, one of America’s premier intellectual publications. By the time he left Europe, Hudson’s work had developed to the point where it would later be included in the International Exposition in Bergen, Norway in 1898 and the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, with his work earning a silver medal in each fair.

When Hudson returned from Europe he began a career in illustration, providing pictures for national magazines and books. Two of the books that he illustrated were “The Forging of the Sword” and other poems by Juan Lewis in 1892 and “A Ranch on the Oxhide.” He also continued writing articles for periodicals like Cosmopolitan and the Atlantic.. Hudson married Christine Schmidt (1869-1972) in 1893 and the following year they had a son, Lester J. Hudson (1894-1974), but the relationship didn’t last.

Hudson had always been interested in the natural world, and he found a second calling by painting illustrations of fish and animals for scientific publications. He illustrated a scholarly work on the preparation of specimens for display in 1891. Because of the quality of his work and his dedication, Hudson was hired to go on expeditions funded by the Bureau of Fisheries. On trips to the Caribbean, the Great Lakes, the rivers of California and the Pacific Coast, he would paint examples of fish as they were caught and identified.

Hudson worked closely with the naturalist David Starr Jordon, first president of Stanford University, who wrote a number of scholarly works on fish with Dr. Barton W. Everman of the Bureau of Fisheries. On a trip to Hawaii with Jordon the artist met a young San Jose schoolteacher named Claire Grace Barnhisel, who was on her way to the islands to teach, and a romantic relationship blossomed between artist and teacher. After working with Hudson on a number of scientific expeditions, Jordon described him as the world’s finest illustrator of marine life – someone who could combine accuracy and beauty – and some of the scholarly volumes they collaborated on are highly sought- after collector’s items today.

In 1898 Hudson put his illustrations, easel paintings and scientific collaboration on hold to join the ranks of volunteers for the Spanish-American War. Commissioned as a lieutenant, he was sent to Cuba, participated in the victorious Siege of Santiago, and then served on the staff of Col. George H. Harries, who led the 1st District of Columbia Infantry. Because the war was so short, the unit saw little action, but Hudson distinguished himself enough to be promoted to Captain, and many people referred to him as “Captain Hudson” for the rest of his life.

Hudson was introduced to the Monterey Peninsula through his scientific work, for even then the region was famous for the incredible variety of marine and mammalian species that populated its shores and sea. The artist was drawn to the area purchasing a home in Pacific Grove, where he brought his new wife Claire after their marriage in December of 1903. Once settled in the coastal hamlet, Hudson began to paint scenes of the sand dunes and flora of the peninsula as well as the ocean, often with the subtle effects of the setting sun. He exhibited at the Del Monte Art Gallery in Monterey, with the local art organizations and sent paintings north to exhibitions at the Bohemian Club and at Gump’s, the antique dealer in San Francisco.

After moving to the Peninsula, Hudson came to love and romanticize the days of the “Californios,” as the residents of Alta California called themselves before the Americans gained control of the state in 1848. In 1915 he did an article for Sunset Magazine titled “California on the Etching Plate” where he wrote wistfully about the days of the Carmel Mission and the Monterey Presidio. Hudson illustrated the article with etchings of some of the historic adobes of the peninsula. Because of his historical interest in early days of Monterey, he became an early preservationist list and an advocate for the timeless Spanish methods of building.

Fortunately, Hudson’s interest in historic preservation was passed onto his children. His oldest son, Lester, lived in Washington D.C., but spent summers with his father in California. While on vacation at one point he met a local girl, Margret MacMillian Allen, who became his wife. The Allens were enlightened ranchers who owned a large parcel of land south of Carmel, which included the dramatic cliffs and bays of Point Lobos. During and after his long and distinguished naval career, Admiral Hudson and his wife were active in preservation efforts and instrumental in the Allen family’s deeding Point Lobos to the state of California.

Settled in his cozy home and studio near the Asilomar resort, Hudson wrote two books, “The Crimson Conquest” (1906) which was a romanticized telling of Pizzaro’s conquest of Peru and “The Royal Outlaw” (1917) a novel for young adults on the biblical story of King David. He continued to write magazine articles and during World War I he wrote a analysis on German militarism for the New York Times Magazine.

After the San Francisco Earthquake the entire city had to be rebuilt, and one of the last major structures to be completed was the San Francisco Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park. Hudson painted some of the large murals that served as the backdrops for the dioramas featuring mounted specimens of the animals of the coast and islands of California. When the academy finally opened in 1916, Hudson’s work was highly praised and remains on display today.

When the Carmel Art Association was formed in 1927, Hudson became a member, and he continued painting into his 60s, even as the artistic elite turned their back on the traditionalist painters. In 1939, the year of the artist’s death, San Francisco hosted the Golden Gate International Exposition. Held twenty-four years after the Panama-Pacific Exposition, this was the San Francisco’s second World’s Fair, and Charles Bradford Hudson’s works were included.

Hudson’s works are rarely on the market, as many remain in the collections of his distinguised family. His artistic oeuvre includes scenes of Monterey, Carmel, Asilomar, the southern California coast an the Mojave Desert, all beautifully painted and subtly colored. An in-depth biography of Charles Bradford Hudson is being perpared by scientist Victor G. Springer of the Smithsonian Institution and author Kristin Murphy. This book will cover his life, artistic and literary accomlishments and numerous contributions to science.

William Keith: From the Grandiose to the Intimate

2011/05/27 § 3 Comments

William Keith

From the Heroic Landscape to Tonalism

By Jeffrey Morseburg

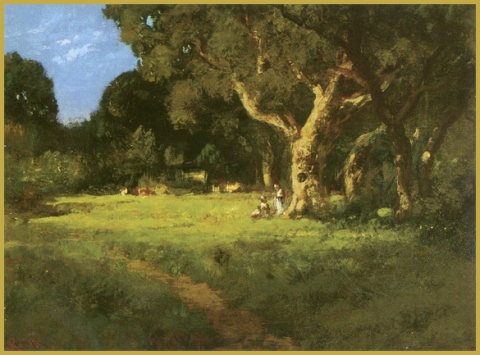

William Keith (1838-1911) is the seminal figure in the history of early California painting. For contemporary viewers, attuned to the colorful palette of California Impressionism, the appeal that Keith has to art historians and collectors may be difficult to understand at first glance. After all, his Barbizon-inspired works were often painted in a narrow tonal range and many of the late works are dark, even murky. However, as viewers become more familiar with his career and the breadth of his artistic output, they should come to understand why Keith was the dominant figure in California painting for several decades and why his best works can be ranked among the great masterpieces of 19th-Century American landscape painting.

William Keith was born in Aberden, Scotland in 1838. He was raised in a strict Presbyterian environment first by his maternal grandparents and then by his mother. In 1852, while he was a teenager, Keith emigrated to America with his mother and sisters. They made their way to New York, where his maternal uncle, William Bruce, had settled. Like many other artistically talented boys of his era, he quit school at an early age and was apprenticed to a wood engraver before joining the Harper Brothers publishing firm.

During Keith’s formative years, New York was the thriving artistic capital of America. The Hudson River School of Romantic landscape painters dominated the artistic scene and the National Academy of Design, which was the main American exhibition venue. The young Scottish emigrant’s artist apprenticeship and early professional career coincided with the triumphs of Frederick Church (1826-1900) and his great rival Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). Church ventured to Central and South America and his romantic pictures of the Andes became a sensation while Bierstadt’s enormous canvasses of the Rocky Mountains brought him fame if not always critical success. Keith ventured west to California in 1859, settling in San Francisco, where he began to scratch out a living as an engraver. It was there that he took his first formal painting lessons, from the noted portrait painter Samuel Mardsen Brooks (1816-1892).

Keith’s growing success in the engraving business enabled him to marry fellow artist, Elizabeth Emerson, in 1864. Two years later he began to exhibit his watercolors professionally. Keith’s chosen medium and the naturalistic handling of his subjects reflect his familiarity with the works and ideals of the British author and painter John Ruskin (1819-1900) and the English movements he influenced. His early works were of Marin County, the domesticated countryside just north of San Francisco, but by 1867 he was painting in the Sierra Nevada, which would become the subject of his greatest works. Soon, the young artist began working in oils, but his early efforts in this medium were somewhat crude and labored. On his sketching trips, he usually worked in oil on paper, waiting until he returned to his San Francisco studio to work the sketches up on canvas. Keith became an experienced outdoorsman, and in early 1869, a commission took him on an extended sketching trip throughout the wilderness of the Pacific Northwest.

Realizing that he needed further formal training, Keith held a successful auction of his works, and in the fall of 1869 left for Europe. In that era, many American painters who aspired to landscape painting chose to study in Dusseldorf, rather than Paris, so it was there that Keith went to study with Albert Flamm (1823-1906). Although Keith’s stay in Europe was brief, lasting less than a year, his formal work with Flamm and his exposure to European exhibitions introduced him to a wide range of artistic styles and helped him to reach artistic maturity.

Keith returned to the United States in 1871. He first painted in rugged Maine, where dozens of the successful New York painters summered. Then opened a studio in Boston. Keith’s large paintings of California began to win him some good notices and a following of patrons. He exhibited major paintings of Mount Tamalpais and Mount Shasta at the National Academy of Design, which were then sold to prominent California collectors. In 1872 Keith returned to San Francisco, a mature and experienced painter. He found that his competitor Thomas Hill (1829-1908) had also returned from a period of study and that in addition the Eastern painter Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) had opened a studio for an extended stay in the west. Together, these three painters built a wide following for their monumental scenes of the Sierra Nevada and other California subjects. Their major works were artistic expressions of the philosophy of American expansionism. As cities were transformed by the forces of the industrial age, the works of Keith and other landscape painters began to reflect an appreciation for the grandeur of the western landscape. Keith’s artistic philosophy was also shaped by his friendship with the naturalist John Muir, whom he accompanied on extended treks through the wilderness.

Elizabeth Keith, the artist’s wife, died in 1882. After marrying the amateur artist Mary McHenry, a restless Keith returned to Europe in 1883, now with the intention of mastering portraiture. Always attracted to a broad technique and darker tonalities, Keith ventured to Munich, where these characteristics were still favored. He opened his own studio in the Bavarian capital and had his work critiqued by some of the leaders of the Munich school. The expatriate American painter J. Frank Currier (1843-1909), for example, encouraged Keith to try a more experimental approach to painting the landscape. This second European sojurn’s exposure to new ideas had a lasting effect on the California atist, and he began to adopt a much more evocative style.

The William Keith that returned to San Francisco was a changed artist. In his later work, influenced by the stay in Munich and the works of the Barbizon painters that he had seen in Paris, Keith placed more emphasis on the mood of his chosen subject and paid less attention to the topography of the landscape. He began to paint simple scenes of sheep grazing on the hills of Marin County or cattle lying in the shady glen. He no longer sought to find the “truth” of nature, but to paint its moods. Unfortunately, these more interpretive paintings did not please the public as much as the more heroic depictions of nature that he had done in earlier years, and Keith went through a period of depression.

In 1891 George Inness (1823-1894), the American Tonalist painter, came west to San Francisco and changed the course of Keith’s career. Keith had been influenced by the writings of Inness, and the two artists shared not only a similar artistic outlook, but even the same Swedenborgian religious philosophy. Inness’s visit lifted the California artist’s spirits and the two men traveled together, shared Keith’s studio, and held a joint exhibition in San Francisco. Keith learned a great deal from Inness, whose stature in American art helped justify the change in style that western audiences had found inscrutable.

As the 1890s progressed, Keith’s popularity grew, and he became one of the most prosperous and respected members of San Francisco’s artistic community. In 1893 his works were exhibited in the Chicago World’s Fair, and he made another extended trip to Europe. Keith’s poetic, pastoral pieces were sold to California’s elite. While Keith painted some masterful paintings in his later years, his artistic oeuvre is littered with poorly composed and overly gloomy landscapes, many of which have turned even darker with the passing of time. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire destroyed Keith’s studio and, tragically, two thousand of his paintings. Unfortunately, many of Keith’s important early works were lost in the conflagration, which also destroyed the homes of most of the important San Francisco collectors. Keith managed to recover from the loss, however, and continued painting until a short time before his death in 1911.

William Keith’s artistic philosophy changed dramatically in the course of his long life. moving from the grandiose to the intimate. He began his career as a painter of the heroic landscape, celebrating California’s beauty and grandeur. As the frontier period of American history closed, and the west was domesticated, Keith turned from a romantic approach to a more subjective and poetic view of nature and he seems to have been the only notable California painter who made this type of transformation. Copyright, 2001-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without the specific written permission of the author. This entry adapted from my brief essay in the California Art Club’s Gold Medal Exhibition Catalog from 2001.

The Two-Fisted Impressionism of Edgar Payne

2011/05/18 § Leave a comment

Edgar Alwyn Payne

From the High Sierras to Laguna Beach

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Edgar Payne (1882-1947) was a California Plein-air Painter who worked in a highly masculine, two-fisted style that is instantly recognizable. He was a prolific artist who is best known for “signature works” of the high mountain lakes of California’s Sierra Nevada, with their cool, sparkling pools kept in shadow by the glaciered peaks. He was almost as well known for his scenes of the California Southland, European fishing boats and paintings of the Navajos in the red-rocked canons of Arizona and New Mexico which are all highly prized by collectors.

Edgar Alwyn Payne was born in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri and he struck out on his own at the age of fourteen. He was always artistically talented and he worked as an itinerant house painter, sign painter and set painter for traveling theatrical productions. While Payne is generally regarded as self-taught, he actually had some formal education during his travels at the Art Institute of Chicago and in Dallas, Texas. He made his first trip to California in 1909, painting in Laguna Beach and visiting in San Francisco where he met Elsie Palmer, an artist who became his wife in Chicago in 1912. In 1917 the Paynes left the Midwest for good, traveling west to Glendale, California where Edgar worked on a vast mural for the Congressional Hotel. In 1918 the Paynes settled in Laguna where they established a studio and Edgar Payne became the founder and first President of the Laguna Art Association, which is now the Laguna Museum of Art. Payne began painting extensively in the Sierras and within a short time he was indelibly associated with this chain of dramatic peaks, the backbone of California. While Payne became a pillar of Laguna’s artistic community, he never stopped traveling, spending some winters in and around New York City and then traveling in Europe for two years. The Great Depression were hard years for artists and even in the twilight of his career, Payne was forced to teach to pay the bills. In an attempt to pass his hard-won knowledge on to younger generations of painters, the aging wrote The Composition of Outdoor Painting, which was published in 1941. Copyright 2001-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without author’s specific written permission.

Ellen Burpee Farr: Pasadena’s Entrepenurial Artist

2011/05/18 § 2 Comments

Ellen Burpee Farr

Early Pasadena Still Life Painter

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Ellen Burpee Farr (1840-1907) was an Early California painter who is known for her still lifes of California poppies, Indian baskets and California citrus and pepper trees, which was her favorite subject. Farr, like a number of other talented women painters, had to delay her artistic career because of the demands of marriage and child rearing, in her case for twenty years. However, after she moved west to Pasadena, she forged a successful career as a fine artist and became a vital member of its cultural community.

Ellen Frances Burpee Farr came from an old New England family, members of which had fought in the American Revolution. She was born on November 14, 1840 and raised in New Hampton, New Hampshire, where her father, Augustus Burpee, was a prominent citizen. She was an artistically talented and independent young woman who went on to graduate from the New Hampshire Institute and the Thetford Academy, near Thetford, Vermont.

The Thetford academy was founded in 1819, and from the beginning it accepted both young men and women. While the purpose of the academy was to prepare boys for college and girls for domestic life and social responsibility, the curriculum was very intense for both sexes, with classical instruction in Latin, Greek and French, English courses and higher mathematics. Because Ellen Burpee was culturally inclined and artistically talented, Thetford’s courses in drawing, painting and music would have appealed to her and enhanced her artistic abilities.

While Burpee excelled in her art classes and clearly had the drive and talent to succeed as a painter, an artistic career wasn’t then considered an option for girls from good families, especially when even the best male painters still struggled financially. She probably graduated with her class in July of 1859, becoming engaged to her future husband, Evarts Worcester Farr (1840-1880), whom she had met at the Academy, the next year.

Evarts Farr was a brilliant young man who enrolled in Dartmouth College after he graduated from Thetford, joining the college’s class of 1864. Unfortunately, the Civil War interrupted his education and the idealistic young Evarts Farr became the first volunteer for the Union Army from his hometown of Littleton, New Hampshire. Evarts Farr and Ellen Burpee were hurriedly married on May 19, 1861, just weeks before the young solider and the 2nd New Hampshire departed from Portsmouth for Washington, on June 20th. In December he was promoted to Captain and placed in command of a Regiment. Some months later, while fighting under General “Fighting Joe” Hooker at Williamsburg, on May 15 of 1862, a musket ball shattered his arm, and battlefield surgeons amputated it above his elbow.

Evarts Farr returned home to his young wife, but after a short recuperation, he could not be dissuaded from returning to the war and took the train south. He served with the second New Hampshire at Harrison’s landing and then returned home to recruit more volunteers. He was soon promoted to Major and returned to the war with the 11th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry. He served at the bloody Battle of Fredericksburg, where he was responsible for having Colonel and future Governor Walter Harriman charged with desertion of his post, prompting his resignation.

While Evarts Farr was engaged in the battle to save the Union, his wife kept the home fires burning. Ellen Burpee Farr had her first child, a daughter named Ida, in 1863, about the time her husband was fighting at the Siege of Vicksburg. Because of his amputation, the Major was transferred to the Judge Advocate General’s Office, where he completed his military service. Ellen Farr’s second child, Herbert, was born in 1865, while her husband completed his martial commitment.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, Evarts Farr returned home to his wife and family. He completed his education while Ellen kept their home and raised their children. Major Farr was admitted to the bar in 1867 and joined his father’s law practice. He became a prominent attorney and in 1872, he and his wife had their third and final child, a girl named Edith. As the wife of a prominent man, Ellen Farr became active in a number of charities and social organizations, primarily the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Order of the Eastern Star, a women’s organization that was affiliated with the Masons. Major Farr became an assessor, a solicitor and then was elected to the United States House of Representatives on the Republican ticket in 1877 and again in 187

Unfortunately, Major Farr fell ill in November of 1880. The illness worsened, and he died of pneumonia. Suddenly, Ellen Burpee Far was without a husband and had three children to raise and support. However, as the widow of a Congressman and a Civil War hero, she had a reservoir of good will and a social prominence that would have helped open some doors for her, and she was a resourceful woman. In the wake of her father’s death, Farr’s seventeen-year-old daughter Ida helped take care of her younger brother Herbert, who was fourteen, and her sister Edith, who was seven.

In 1883, a few years after her husband’s death, Farr moved her family to Boston where she began to apply herself to the study of art, hoping to be able to help support her family through her artistic talents. Farr is credited with studying with the academically trained French painter Louis-Mathieu Didier Guillaume (1816-1892), who lived in Richmond during the Civil War and then moved to Washington D.C. in 1871, and then, presumably, on to Boston for a time. A look at Guillaume’s work is enlightening because he specialized in portraits and still lifes and one can assume that Farr’s studies with the French painter were a great influence on the course of her career and her choice of subjects.

Farr began to forge a career as a still life painter in Boston, apparently selling works to friends and acquaintances back in New Hampshire. She may have concentrated on the genre because she was more drawn to these domestic subjects, or perhaps because the demands of landscape painting was too difficult for a woman who still had children at home. Farr’s early still lifes were more formal than her later works, some of them more European in conception and others, game still life’s for example, clearly influenced by the works of William Michael Harnett (1848-1892) and the American Trompe l’oeil movement. By the time Farr began to apply herself to art, her artistically talented daughter Ida was also studying, attending the Museum School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and attending Wellesley College.

Farr moved west to Pasadena, California in 1887. At the encouragement C.H. Merrill, the manager of South Pasadena’s new Raymond Hotel, whom she may have known when he managed resorts in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, she opened a studio and gallery in the hotel, which was popular with the Eastern carriage trade. Farr was a perceptive businesswoman and she realized that the eastern visitors who wintered in Pasadena wanted reminders of their visit to the Southland, so she filled her still lifes with iconic California mementos. Her paintings featured California oranges on the vine, woven Indian baskets, Mexican tamales and chilis, and the pepper trees that lined the grounds of the missions and some of the other Spanish Colonial buildings. Farr also painted some landscapes, usually of the local missions, which were also popular subjects with Eastern tourists.

Farr threw herself into the civic and cultural life of her adopted home, founding the Young Women’s Business League of Pasadena. She was also active with the Shakespeare Club of Pasadena and is credited with designing its distinctive clubhouse. In 1894, she camped and painted on Santa Catalina Island, a playground of the wealthy, setting up an exotic tented studio. The huge Raymond Hotel was consumed by fire in 1895 and Farr purchased an abandoned vineyard in Pasadena with an old adobe home that same year. She restored the house and built a beautiful atelier, filled with fascinating objects for her still lifes, and planted gardens with the pepper trees that were her favorite subject.

In 1906 Farr left Pasadena for Europe, intending to take a two-year Grand Tour of the continent, to visit the great art museums and see the classical ruins of France and Italy. Unfortunately, she died suddenly while she was visiting Naples, on January 5, 1907. Copyright, 2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without author’s specific written permission.

The San Francisco Portraits of Walter Cox

2011/05/18 § Leave a comment

Walter Ignatius Cox

San Francisco Portrait Painter

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Walter Ignatius Cox (1867-1930) was an English-born California painter who seems to have thus far escaped scholarly notice. While he painted the garden scenes and domesticated landscapes that are more frequently seen today, during his lifetime he was primarily known for his formal portraits. His tranquil landscapes show an awareness of Impressionism and a brighter palette, but maintain a solid sense of construction that is academic in origin. His landscapes, usually of gardens, front porches, parks and scenes of al fresco dining, have an innocent, almost naïve quality.

Cox was born in Broxwood Court, Hertsfordshire in England, on May 4, 1867 to Richard Snead Cox (1820-1899) and Maria Teresa Weld Cox (1828-1886). He came from an old English family who were descendants of the Plantagenet Kings. The Cox family was part of the Catholic minority and young Walter was educated at St. Gregory’s College, a Catholic boarding school in Somerset, in Southwest England. Because of his artistic talent, after completing his secondary education he moved to Paris. In the French capital he studied at the private Academie Julian under the grand history painters Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902) and Jules-Joseph Lefebvre (1836-1911), as well as the titan of the French Academy, William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905).

After the completion of his studies, Cox established himself as portrait painter in London, opening a studio in fashionable Chelsea. A number of prominent British subjects sat for him, including Cardinal Herbert Alfred Vaughn of London (1832-1903), who may have preferred a painter with a Catholic background. For the remainder of his career Cox would maintain good relations with the Catholic hierarchy, and he painted the official portraits of a number of Archbishops and Cardinals.

Cox married Lavina Carton Millet (1869-1933) of Hampshire in 1897. The couple immigrated to the United States in 1904, settling in San Francisco, where Cox opened a portrait studio on Van Ness Avenue. He and his wife resided on Jackson Street. In San Francisco he became part of the downtown milieu of bohemian artists and writers. He also established a relationship with the Catholic Church, and painted Archbishop Patrick William Riordan (1841-1914) and Archbishop George Montgomery (1847-1907), who came to the aid of the city and rebuilt the local parishes after the San Francisco Earthquake.

Cox traveled to Victoria, British Columbia in 1905, where he painted Archbishop Bertram Orth (in office 1903-1908) and a number of judges and other public officials. His San Francisco studio was frequently in the papers and he was well known for painting fashionable women. He completed society portraits of Mrs. Maria Inez Shorb White (1868-1933) of San Gabriel, Miss Sarah Bell Collier and Miss Betsy Angus (later Mrs. St. George Holden) of San Francisco and other members of California’s elite who were well known in those days.

Because of his French academic training, Cox had the ambitions to be a “history painter” like his instructors at the Academie Julian. In Paris and London he had also come under the spell of the Orientalist movement, and he painted compositions drawn from biblical history. According to contemporary accounts, soon after his arrival he began working on an ambitious painting of the notables of San Francisco that was nine feet high by twelve feet wide, with hundreds of figures. Another work in progress was a scene of the Crucifixion of Christ, a grand history painting in the French manner, with the dramatic event depicted at the moment when darkness enveloped Jerusalem. Cox also painted a large composition of Gregory the Great in the Roman slave market.

Unfortunately, just as Cox was establishing himself in the Bay Area, the 1906 earthquake struck, followed by the conflagration, and like most of the other residents he lost almost everything, including the major works described above. His small cottage, located on Sacramento, street, near the intersection of Franklin and Van Ness, was one of the last to be consumed by the out-of-control fire. The loss of an artist’s production meant that not only was his inventory gone, but also his creative history, his sketches, studies, and sample portraits. The Oakland Tribune dramatized the situation of the artists and sculptors for its readers, who had watched the catastrophe from across the bay with horror:

A palace razed to the ground may be reconstructed within a few months. An immense emporium with its contents may be utterly effaced, but a thousand hands and machines without number, within a comparatively short time can rebuild the one more beautifully and restock the other as it never had been stocked before.

Such however is not a possibility in the world of art. The studios of San Francisco which were destroyed – and they were all laid in common ruin – represented the work of years not only of the owners, but also of the kindred souls possessed of genius and the restoration of them and their contents can be accomplished only by hand.

After the disaster, some painters fled south to Carmel, while others, like Cox, crossed the water and set up new studios in the East Bay. The portrait painter leased a new studio in the El Granada, at the intersection of Bancroft Way and Telegraph in Berkeley, and his wife set up their new living quarters in an adjacent apartment. In Berkeley, the artist began painting portraits to replace those lost in the great earthquake and also opened art classes for local residents, but Cox and his wife soon returned to San Francisco, establishing another studio on Van Ness Avenue.

Walter and Lavina Cox were frequently in the society pages of the San Francisco and East Bay newspapers. The papers noted that the couple was dressed smartly at the opera or was seen at the Tea Room of the St. Francis Hotel, which was frequented by the “smart set.” The painter was successful enough to have a summer studio in the Easton neighborhood of Burlingame, where he painted landscapes and attempted to take a break from his portrait commissions. Cox concentrated on portraits during the fall and winter months so that he could make sketching trips during the spring and summer months. He took trips to his native England and Scotland, bringing back watercolors and landscape studies which he sold to collectors in the Bay Area. Cox also made trips to Mexico, stopping in Los Angeles along the way, where he had portrait clients.

In 1912 Cox painted the famous novelist Gertrude Atherton (1857-1948), which resulted in a bounty of publicity for the artist. The large portrait was reproduced in the San Francisco papers, exhibited in his studio and hung in the Tea Room of the St. Francis Hotel for a high society reception. He completed a life-size portrait of the socialite Miss Hazel King and portraits of Miss Julia Langhorne, Mrs. Tom Williams and her daughters and William Ronaldson, all well-known social figures of the era. Cox sold most of his work from his own well-appointed studio, but he also exhibited at Kilbey’s in San Francisco and had an exhibition at the Palace Hotel in 1914.

There is no record that Cox exhibited at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the San Francisco World’s Fair. This may be because Cox was still considered a British painter and thus not eligible for inclusion, but it is probable that by the time of the exposition he and his wife had already left San Francisco for New York, where they lived for a number of years. In the east, he continued painting portraits for the Catholic Church as well as of political figures. His last studio was in the Washington D.C. suburb of Alexandria, where he did portraits of important Washingtonians. Lavina Cox, the painter’s wife, returned to England to care for an aunt in the 1920s and never returned to her husband in America, remaining there until she passed away in 1933.

Like many society painters, he was described as “genial and gentlemanly” and having the “faculty for making friends by his personality as well as creating admirers by his brush.” Cox was known for achieving a good likeness and many of his commissions were for full-length portraits in the grand manner. His upbringing and education gave him a scholarly air which gave his sitter’s confidence in his taste as well as his artistic ability. Those who sat for portraits by Cox included President Warren J. Harding (1865-1923) and former President and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court William Taft (1857-1930). Copyright 2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without author’s specific written permission.

The Artistic Atmosphere of Sam Hyde Harris

2011/05/18 § Leave a comment

Sam Hyde Harris

The Atmosphere of the Southland

California Art Club

by Jeffrey Morseburg

Sam Hyde Harris (1889-1978) was one of the best-known artists of the San Gabriel Valley – the painters who lived beneath Mt. Wilson and the peaks of the San Gabriel Mountains, northeast of Los Angeles. He is best known for his works of the 1920s and 1930s – paintings that are alive with the unique atmosphere of Los Angeles. Harris had the ability to capture the morning overcast that enveloped the local foothills, the layer of smoke and dust that the Santa Ana winds bring to the arid valleys of the Southland. However, he was equally adept at capturing the rustic beauty of the Carmel Peninsula or the Laguna Coast, where the sun plays “hide and seek” with the mist and clouds. Harris was known for works that were memorably composed and that had a clear, crisp, but limited palette that honestly portrayed the conditions he found out-of-doors. He believed in verisimilitude, in recording the truth of what he saw in the desert, mountains and coasts of his beloved California.

Sam Hyde Harris was born in Middlesex, England in 1889, but immigrated to the United States with his family in 1904. His speech bore traces of his British origins the rest of his life. Harris was so artistically gifted that he began working as a commercial artist as a teenager, and he carried a letter of recommendation from his British employer when he settled in Los Angeles at the age of fifteen. He was an industrious young man and he worked as a sign painter, designer and commercial artist for different firms before opening his own studio in 1914.

Although the young immigrant was already a successful commercial artist, he wanted to be a fine artist and master the depiction of the rugged land that was new to him, so he enrolled in classes at the Los Angeles Art Students League and the Canon Art School, where he studied with the Impressionist painters Frank Tolles Chamberlin (1873-1961) and Hanson Duvall Puthuff (1875-1972), and the early modernist Stanton McDonald-Wright (1890-1973). Harris began working with Puthuff in 1906 and the two became life-long friends and comrades, traveling all over California in pursuit of the highly atmospheric moods that they loved the challenge of capturing.

While Harris was designing the orange crate labels that became a symbol of the good life in California to beleaguered citrus lovers in colder climes and his beautifully composed promotional posters for the Union Pacific and Santa Fe Railroads, he gained confidence in his easel paintings and began exhibiting his plein-air works. His first recorded exhibition was in 1920 with the California Art Club and for the rest of his life, he exhibited with great regularity.

In addition to painting with Hanson Puthuff, Harris also traveled and painted with Jean Mannheim (1862-1945) and Edgar Payne (1883-1947). In contrast to many of his fellow artists, Harris also liked to paint urban landscapes and he did many paintings of the old farms of the San Gabriel Valley as well as the east side of Los Angeles. He did some wonderfully atmospheric paintings of the old barrios of Chavez Ravine, where Dodger Stadium was eventually built, and the finest of these works is in the collection of the O’Malley family, who owned the Dodgers and brought them to Los Angeles.

In the 1930s Harris began painting the waterfronts of Newport Beach, San Pedro, Sunset Beach and even San Diego. Most of these works depicted anchored boats and the lazy waterfront in the morning overcast. As the years progressed he fell in love with the desert, traveling east to the low desert around Indio and Palm Springs in the company of other painters like Jimmy Swinnerton (1875-1974), Jack Wilkinson Smith, and Victor Matson (1895-1972). In his later years, Harris altered his technique and his work became harder edged and more economical, but he maintained the same emphasis on capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the area he was painting.

Harris was part of the small Alhambra art colony that had developed around Champion Place, at the east end of San Gabriel Valley community of Alhambra, hard against the old wash that carried water from the mountains during the rainy season. The group of Alhambra artists included the painter and cartoonist Clyde Forsyth (1885-1962), the western painter Frank Tenney Johnson (1888-1939), Jack Wilkinson Smith (1873-1949), and the sculptor Eli Harvey (1860-1957). Famed illustrator Norman Rockwell was a summer resident. Harris lived near Champion Place on Hidalgo Street, but took over Jack Smith’s old “Artist’s Alley” studio in 1949.

Harris was one of the few major California plein-air painters who lived into the 1970s, and only a few years after his passing his work began to be rediscovered along with that of his friends and comrades in the California Impressionist movement. In 1980 Harris was the subject of one of the first retrospective exhibitions devoted to a California Plein-Air painter, when the much-missed Peterson Galleries in Beverly Hills mounted an exhibition curated by the art historian Jean Stern.

Sam Hyde Harris was a member of the seminal California Art Club, the Painters and Sculptors Club and the Laguna Beach Art Association. During his long career he won many awards at major exhibitions. His work is in the collections of virtually every major institution that collects California Impressionism, including the Irvine Museum and Fleisher Collection as well as major private collections across the United States. He was the subject of a major retrospective at the Pasadena Museum of History in 2007 and 2008 and a large book was produced to accompany the exhibition. Copyright, 2010-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without author’s express written permission.

The Decorative Impressionism of Richard E. Miller

2011/05/18 § Leave a comment

Richard E. Miller

The Decorative Impressionism of the Giverny School

National Academy of Design

California Art Club

by Jeffrey Morseburg

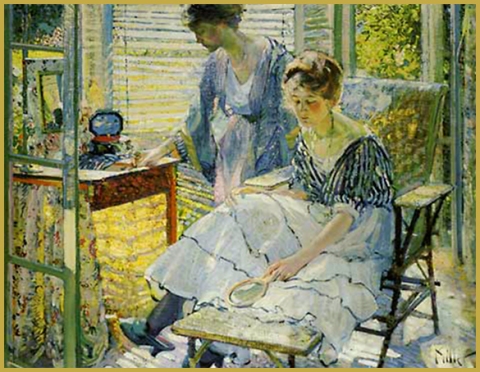

Although Richard Edward Miller (1875-1943) only spent a short time in California, his distinctive painting style and teaching appointment at Pasadena’s Stickney’s School influenced younger southland painters. Miller’s works are characterized by a strong decorative element. Although he was a member of the art colony that sprang up around Claude Monet in Giverny, Miller never fully rejected the academic principles he learned in Paris and dissolved form into color and light. He never abandoned formal pictorial elements, favored compositions centered on beautiful women who are lost in thought and are dramatically back-lit by intense sunlight streaming through French doors.

Strongly influenced by James Whistler and the Aesthetic Movement, Miller rejected the Victorian-age emphasis on narrative content and worked instead at conveying what he described as a ‘pleasant optical sensation.’ Miller’s were never haphazard arrangements of elements that he painted alla-prima- they were carefully composed. Miller once said, “Atmosphere and color are never permanent. Paint won’t remain the same color forever. But the design will stay. And that is the creative part of it.” As artistic styles changed, Miller never strayed from his conviction that art was about ‘the creation of beauty.’

Richard Miller was born in the waterfront city of St. Louis in 1875. He grew up in a culturally rich environment and bean painting seriously at an early age. Initially, Miller worked as a helper for the portrait painter, George Eichbaum and received encouragement from his neighbor, ,Oscar Berninghaus (1874 – 1952).

Despite his father’s reluctance, Miller enrolled at the School of Fine Arts at Washington University. He studied at the St. Louis School with Edmund H. Wuerpel (1866 – 1958), a tonalist painter who had recently returned from France. To support himself during his studies, Miller worked as as commercial artist. Concluding his St. Louis studies in 1897, he saved money and sailed for Paris in 1899 with a scholarship in hand.

Like many other American artists, Miller went to the Parisian art capital to build on the knowledge he had obtained in the United States. First, he enrolled at the private Academie Julian, where he studied under Jean-Paul Laurens (1838 – 1921) and Benjamin Constant (1845 – 1902). After a year of study ‘working from the nude,’ Miller had a painting accepted at the Salon and won a third place medal.

Miller struggled financially in Paris and even returned to St. Louis to teach for a year between 1901 and 1902. Back in Paris, Miller came under the spell of Whistler, whom he admired for his emphasis on design, his tonal and color harmonies and the eccentric painter’s ‘art for art’s sake’ ideal. Like Whistler, the young St. Louis painter was influenced by the simple sophistication of Japanese prints. Miller’s early French works exhibit these influences with their beautiful quality of line and quiet tonalities.

As me matured, Miller began to explore more dynamic color relationships. His works became bolder, though still harmonious, with a bravura brushwork that may show the influence of the Spanish artist, Joaquin Sorolla (1863 – 1923). By 1907, Miller had become a member of the Giverny colony of American Impressionists, where his friends and fellow artists, Guy Rose and Lawton Parker (1860 – 1954), had settled. Miller reached his mature style in Giverny, adopting a flatter, even more decorative approach to the figure.

Miller and his Giverny friend, Frederick Frieseke (1874 – 1939) , had a triumphant exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1909. Miller’s rich, colorful paintings, with their exotic fabrics, found a steady market in America. He taught at the Academie Colarossi in Paris and sent paintings back to New York galleries. Like many other painters, Miller was driven home by the outbreak of World War I, when his career was at his peak.

Back in America and at loose ends, Miller painted portraits and served on an Advisory Committee for the Panama-Pacific Exposition and was elected to the National Academy. He joined his friend, Guy Rose, in Pasadena, where they taught at the Stickney School. Miller had great difficulty in finding a studio to paint in, so he borrowed that of Eva Scott Fenyes (1846 – 1930), the present site of the Pasadena Historical Society and Museum. At the Fenyes mansion, Miller painted several characteristic works, some featuring the estate’s lush gardens and fountain.

Miller put down roots in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a picturesque fishing village on Cape Cod, where many other painters had already settled. He became a leader of the more traditionally minded art community in Provincetown, as well as one of its most sought after teachers Miller returned to France briefly, but remained in Provincetown for the rest of his career, returning to the nude and a series of naturalistic portraits late in his career. He died in Cape Cod in 1943. Copyright 2001-2011, Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without author’s specific written permission.

William Wendt: The Sculpted Landscape

2011/05/18 § 1 Comment

William Wendt

The Founding Father of California Impressionism

Founder and President of the California Art Club

by Jeffrey Morseburg

In the history of California Impressionism, William Wendt (1865-1946) was the one indispensable figure. Because of the quality of his bold, masculine landscapes and his many abilities as a leader, the art scene in southern California coalesced around the figure of the quiet, sober German immigrant. William Wendt’s mature style reduced the elements that he saw in nature to broad forms. His short, vigorous brushstrokes gave a heroic solidity to the hills and rocky outcroppings that he favored in his work.

Wendt’s works were rarely panoramic, for he liked to get close to paint. When he painted a hill near Laguna Beach or Morro Bay, the size of it in relation to the size of the composition gave the image an iconic quality. It was this ‘big picture’ approach of Wendt’s that made his the artist that eastern or western viewers thought of when the considered the California landscape.

Wendt was a deeply religious man and his love of nature was reflected in each and every painting, and a number of his works were given religious titles. With little deviation, Wendt took his compositions directly from what he saw on location. He was not one who felt he could ‘improve’ on what God created. The ‘style’ that we know him for today was not a labored attempt at finding a mannered way to paint but the natural outgrowth of his unique artistic voice.

William Wendt was born in Bentzen, Prussia, in 1865- soon to be a part of the re-unified Germany. He attended rural schools and worked unhappily as a cabinet-maker’s apprentice before immigrating to America at the age of fifteen. Wendt joined an uncle in Chicago, where he attended school and began working as a commercial artist.

With only a few evening classes at the Art Institute of Chicago for formal training, Wendt began painting out-of-doors in his spare time. His earliest works was in the tonalist style, then favored by leading American painters. In 1893, he won the Yerkes prize in the Annual Society of Chicago Artists Exhibition, an event that helped launch his professional career.

Wendt made extended painting trips to California with fellow painter, George Gardner Symons (1862 – 1930) in 1894 and 1896. At the request of the Rindge family, he painted a series of canvases on Rancho Malibu in 1897. In 1899, he held an impressive show of his works of California in conjunction with its 12th Annual Exhibition.

It was clear that Wendt had fallen in love with the California landscape, but it was not until 1906 that he put down his roots in southern California, purchasing Elmer and Marion Wachtel’s home in the Highland Park district. He brought his new bride, the sculptor, Julia Bracken Wendt (1871 – 1992), home with him to California. Wendt forged a successful career in the Golden State and was one of the few California artists to build a following in the Midwest and the east.

Wendt was instrumental in the founding of the California Art Club, the organization most responsible for the dissemination of the Impressionist aesthetic in southern California. He served as president for six terms, a record in the early years of the organization. Wendt opened his Laguna Beach studio I 1912 and helped form the Laguna Beach Art Association eight years later. It was Wendt’s skill and reputation that helped popularize plein-air Impressionism in California eighty years ago, and he remains its most original voice today. Copyright, 2001-2011,Jeffrey Morseburg, not to be reproduced without author’s specific written permission.